The fourth issue of pinknantucket press’s Materiality journal (funded by a Pozible campaign) is now available to buy in hard copy and digital form. The theme for this issue is ‘surface’, and the contributors have approached the topic in all kinds of fascinating ways. Also check out the recent ‘speaking scars’ series on the pinknantucket press blog.

“The story of the book as technology must be told honestly, without triumphalism or defeatism”

Selling a book, print or digital, turns out to be far from the only way to generate revenue from all the remarkable cultural activity that goes into the creation and dissemination of literature and ideas.

Richard Nash’s essay on capturing the value of a book

is as affirming as it is alarming in its examination of the economics of literary creation.

“(Will Self’s) Umbrella did not convince me that the dominance of conventional narrative is evidence of cowardice or feeble-mindedness in readers or writers”

Umbrella is undeniably difficult reading, although I found it less and less taxing as I went, a phenomenon that had something to do with the book teaching me how to read it, but probably more to do with a slight easing of Self’s stylistic zealotry somewhere around page fifty. I had the sense that, despite himself, Self became invested in conveying a story. Scenes became longer; characters had decipherable conversations; events caused other events. Any sentence might end by teleporting you from 1971 to 1918, but once you got your bearings, the plot picked up more or less where it left off the last time you’d been in that particular era.

There’s a slightly defensive tone to Maggie Shipstead’s review of Will Self’s modernist novel Umbrella, but it’s nevertheless interesting to note the way in which Self lets narrative intrude

on his experimental opus. The sequences I enjoyed and admired the most were invariably those in which characters engaged in recognisable action and dialogue with each other; turning points in ‘the story’, rendered more or less as conventional ‘scenes’, but composed in the (mostly) uncompromising style that this novel demanded Self invent for it.

“What the internet portends is not the end of the paper container of the book, but rather the way paper organized our assumptions about writing altogether”

I have several reasons for thinking that the current round of destruction is clearing the decks for something better, but the main one is that historically, media that increase the amount of arguing people do has been a long-term positive for society, even at the cost of short-term destruction of familiar patterns, and the disorientation of the people comfortable with those patterns. I think we’ll get extended narrative online — I just doubt the format of most of those narratives will look enough like a book to merit the name.

An excerpt from Clay Shirky’s ongoing exchange with Nicholas Carr about the future of the book in a digital world.

Materiality No. 1 has materialised!

Each generation decides anew what it is about a thing — a book, a pamphlet, a photograph album — that is most significant and makes decisions about its fate accordingly.

Publisher and editor of pinknantucket press, Alice Cannon, in her editorial for the inaugural edition of Materiality — a themed journal that includes fiction, essay, images and poetry, focusing on the physical and material

. The highly-anticipated first edition contains, in Alice’s own words, (m)any things, by excellent people

. I’m hardly likely to argue, given that one of those things is by me. That’s right — I’m officially (or at least materially) excellent!

There are indeed many excellent people contributing to this most excellent venture. I’m particularly looking forward to reading Carolyn Fraser’s essay on nineteenth-century competitive typesetting.

Okay, and the two pieces about reading on the dunny.

A paper and digital bundle of Materiality No. 1 is available at the pinknantucket press online shop.

“Cheap gimmicks and unnecessary tricks”

Pushing the boundaries of what a book is — whether it’s by blurring the lines between different kinds of media or questioning the linear nature of traditional narrative — is not something that people are looking to book publishers to provide. Too much of what we call innovation is basically turning our content into a showroom for device manufacturers — and we do it to the detriment of more important and more useful innovation at the back end of the publishing business.

Joel Naoum of Pan Macmillan’s digital-only imprint Momentum, arguing that publishers are bolting technology onto the wrong parts of their business. Kind of like if the Borg from Star Trek diverted attention from their cube-ship program in favour of giving themselves shiny new genital attachments, but then realised their decreased mobility meant they had no way of getting those genital attachments into the right sockets.

Kind of like that.

“Amazon is great when you know what you’re looking for but hopeless for browsing”

Anna Baddely, editor of the Omnivore, writing in The Guardian on the relative inconspicuousness of digital backlist titles on ebook retailer sites compared with new release titles, and whether this suggests a gap in the market for a virtual “secondhand” bookshop

.

“While parents are pulling the purse strings, it is they that booksellers must appease”

Author James Dawson on balancing a realistic portrayal of teenagers (and swearing) in teen fiction against the objections of gatekeepers, arguably the most powerful link in the publishing chain

:

Interestingly ‘shit’ was only allowed as a curse, not as a bodily function (all bodily functions were removed at the edit, to make the characters more aspirational). It was only when editing my new, second novel that I asked if I could use even stronger swear words in an extreme situation of peril.

Egon Riss’s Penguin Donkey

Despite it having a name that makes it sound like a particularly nauseating carnival sideshow exhibit, I’d really like to own one of these. (Image via Core 77)

“Not all books respond to light damage at the same rate”

If entropy had a gang and ordered a hit on a guy, light would feed the victim hamburgers until he died of organ failure.

This truly inspired analogy can be found in part nine of pinknantucket press’s series on ‘the enemies of books’. If you’ve ever wondered why the photos on the front of travel agency brochures sometimes look uninvitingly drained of life, here’s where you’ll find the answer.

“Writing a novel — actually picking the words and filling in paragraphs — is a tremendous pain in the ass”

Writing a novel – actually picking the words and filling in paragraphs – is a tremendous pain in the ass. Now that TV’s so good and the Internet is an endless forest of distraction, it’s damn near impossible. That should be taken into account when ranking the all-time greats. Somebody like Charles Dickens, for example, who had nothing better to do except eat mutton and attend public hangings, should get very little credit.

“We can’t be so excited over something new and shiny that we knowingly leave people on the other side”

(It’s) difficult for us, on this side of the digital divide, to remember that there are people standing on the other side of what can seem like an impassable gorge, wondering if they’re going to be left behind. Right now, more than 20% of Americans do not have access to the internet. In case that seems like a low number, consider this: That’s one person in five. One person in five doesn’t have access to the internet. Of those who do have access, many have it via shared computers, or via public places like libraries, which allow public use of their machines. […]

Now. How many of these people do you think have access to an ebook reader?

Author Seanan McGuire asks those who would declare the death of print to bear in mind the division between technological haves and have-nots. Recommended. (Via @pinknantucket)

“Buy the atoms, get the bits free”

I’ve seen a lot of people link to Nicholas Carr’s call for publishers to bundle free, electronic versions of books with purchases of the physical artifact (in the way that music labels often bundle audio files with vinyl purchases), but it chimes so much with my own feelings that I felt I needed to link to it here too.

“For the sheet of paper bore only a drawing, of a single, giant, yellow, staring EYE”

‘Good God, man, what do you mean?!’ cried Sergeant Major General. ‘Do you mean some unimaginable alien being came through a hole in the fabric of space-time and sucked this man’s living heart from his body as part of some kind of plot to take over our planet?’

Inspired the acquisition of a number of books all named The Eye of the Tiger, Pinknantucket Press is making its own splendid contribution to the canon of works endowed with this most excellent designation.

Keep a look-out for the forthcoming Eye of the Tiger Omnibus.

“Books can open up emotional, imaginative and historical landscapes that equal and extend the corridors of the web”

Psychologists from Washington University used brain scans to see what happens inside our heads when we read stories. They found that ‘readers mentally simulate each new situation encountered in a narrative’. The brain weaves these situations together with experiences from its own life to create a new mental synthesis. Reading a book leaves us with new neural pathways.

Gail Rebuck in the Guardian on the role of written narrative in developing empathy and a sense of self. She adds that (as) publishers, we need to use every new piece of technology to embed long-form reading within our culture. We should concentrate on the message, not agonise over the medium. We should be agnostic on the platform, but evangelical about the content.

“When they use social media, authors have as many personae to choose from as they do in their other writings”

Every writer is two people (at least). There’s the one that does the writing, and the one that has an egg for breakfast. I’m the other one.

Margaret Atwood on the psychic division between the writer as author and the writer as human being, quoted in the New York Times in the context of authors extending their private selves into the world via social media.

“You don’t need to write a novel in tweets to write a novel about the experience of living in the age of Twitter.”

(W)hat we can expect from books is what the internet has always given us. More. More of everything. But what of taking in continuous prose, in the form conventionally known as “reading”?

Yes, it’s another article about ‘the death of books’ and dwindling attention spans, but Sam Leith seems less anguished than most, and in this piece for the Guardian he touches on an interesting aspect of the rise of digital books — namely the way in which traditional book formats have come about by ‘cultural accident’, and whether emerging formats will have as profound an effect on the nature of prose narrative as have the physical constraints of conventional books.

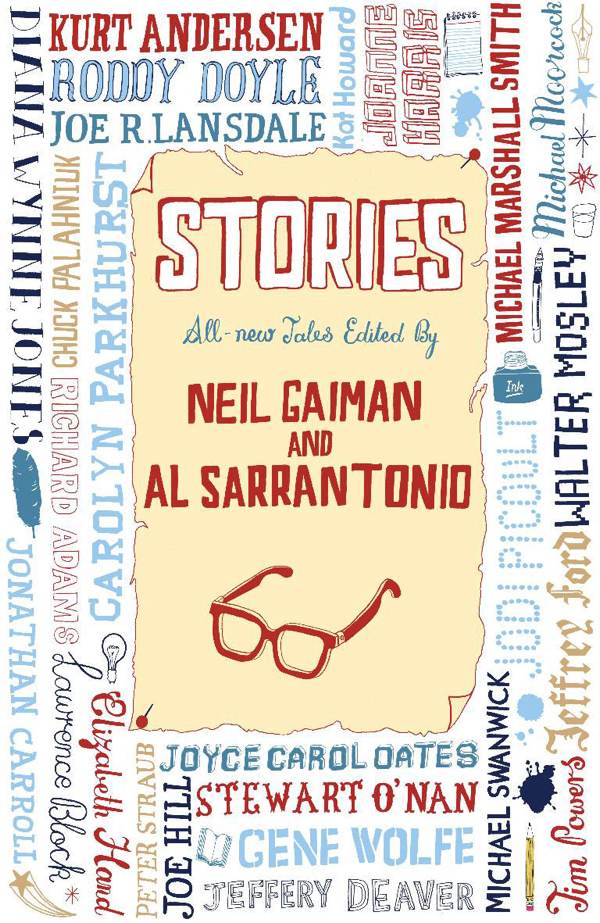

“You only had to survive one of your regrets”

Pharmacists live in minutiae… Ask anyone who has ever filled the innards of a tiny gelatin capsule with a drug, and they will know that twenty grains equals one scruple. Three scruples equal one dram apothecaries. Eight drams apothecaries equal one ounce apothecaries, which equals four hundred eighty grains, or twenty-four scruples.

[…] It was funny — a scruple, by itself, was a misgiving; make it plural and it suddenly was a set of principles, of ethics. […] You only had to survive one of your regrets, and it was enough to make you realize you’d been living your life all wrong.

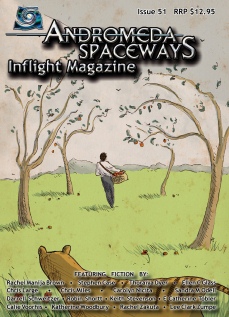

“Chris Miles’ cheeky fusion of fae and suburbia”

My short story ‘The Household Debt’ is among the many tales of fantasy, horror and science-fiction in the latest Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine. Editor Simon Petrie kindly namechecks my piece in his blog post introducing the issue, aptly describing it as a ‘cheeky fusion of fae and suburbia’. It’s also my first full-length speculative fiction story sale.

If you’re not aware of it, ASIM is edited by a cooperative whose members (many of whom are celebrated genre authors in their own right) take turns to oversee the selection of stories for an individual issue. It’s one of the (if not the) most regular print outlets for genre fiction in Australia, publishing local and international authors, and I’m thrilled that my story has found a home within its pages.

I haven’t had a chance to read issue 51 cover to cover, but so far I’ve been very impressed by fellow newcomer Robin Shortt’s ‘Bonsai’, and am looking forward to reading the Keith Stevenson and Thoraiya Dyer pieces.

And if I may be so crass, print ($12.95) and PDF ($4.95) copies of ASIM 51 can be purchased at andromedaspaceways.com.

Web standards and workflows for e-books

Joe Clark on web standards and workflows for e-books in the latest A List Apart:

The canonical format of a book should be HTML. Authors should write in HTML, making a manuscript immediately transformable to an E-book [sic]. A manuscript could then be imported into that fossil the publishing industry refuses to leave behind, Microsoft Word.

Yes yes yes, a thousand times yes. This should have started happening about five years ago. (The section from which this quote is taken is about halfway through the article.)

HTML is a pretty good language for describing the contents of a book (it would be even better if it had a decent way of captioning images) — and in my opinion it’s easy enough to learn that authors (or the editor, or production manager) could render the first draft as a machine-readable document at the beginning of the production process, rather than at the end.

I also learned something new reading this piece: namely, that Unicode has a specification for different width spaces. Colour me the colour of a person who has just found out something they didn’t previously know.